I often have patients who come to see me for neck pain. I will do some manual therapy on their neck muscles and adjust some of the joints in their neck -- and they walk out feeling amazing! Then I'll see them a few days later -- and their neck has tightened back up again.

Patients often ask me, "Why is my neck always tight?" I tell them that one of the major contributors to chronic neck pain and tightness is poor breathing mechanics. At this point, they normally look at me like I have two heads. They may say, "Well, I'm alive -- so how can I be breathing wrong?"

In this blog, I'm going to cover how poor breathing mechanics contribute to neck pain and what to do to fix it. (add in a separator line here to note the Blog beginning)

The Body's Ability to Adapt - Good AND Bad

Our bodies are pretty amazing. One thing that makes our body so amazing is its ability to adapt. Without this ability, when we sprained our ankles, we would be confined to a wheelchair. Instead--our body figures out a way to walk without putting weight on our injured ankle - what we would call a limp.

But sometimes this ability to adapt can lead to problems. Imagine if you sprained your ankle when you were 12 -- and your body decided to limp for the rest of your life. Eventually, the changes your body made to not put weight on your injured ankle would start to overload the other areas of your body and possibly lead to pain and injury.

The same thing can happen when we change our breathing mechanics. The primary muscle that's supposed to be used for breathing is the diaphragm. The diaphragm sits at the bottom of our rib cage and is shaped like an upside-down bowl. When the diaphragm contracts, it drops down and creates negative pressure in the chest. That makes us suck air in through our mouth and nose and fills our lungs with precious oxygen.

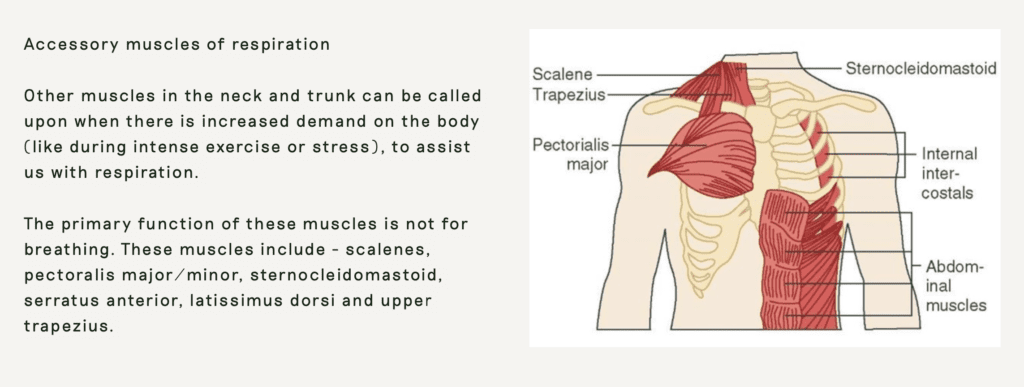

Even though the diaphragm is our body's primary muscle for breathing, we also have lots of other muscles that are called secondary (or accessory) muscles of breathing. These muscles are supposed to be called upon only in times of great oxygen demand. After vigorous exercise, these secondary muscles help to increase the amount of oxygen coming into the lungs to help us recover from the exertion.

Problems occur when people start to use these secondary muscles of breathing all the time. These muscles are only designed to assist in breathing occasionally, and are not to be used 24/7 while we breathe in and out all day long. These muscles are much smaller than the diaphragm and can fatigue much more easily than the diaphragm.

If you look at the picture above, you'll see that it shows these secondary muscles of breathing. Many of them are around our chest and neck. Breathing mechanics that overuse these muscles can lead to tightness and soreness in these areas. The average human breathes 20,000 times a day. So if you use these muscles to breathe all the time, they get a 20,000 rep workout every day. Imagine what your biceps would feel like if you did 20,000 bicep curls every day! They'd probably be pretty sore and tight.

When we primarily use our secondary muscles of breathing, that's called a chest-breathing pattern. Instead of using the diaphragm to drop down and create negative pressure in the chest, we elevate our rib cage to create that negative pressure in the chest. This pattern not only leads to the tightness that I was talking about; it is also a less-efficient breathing pattern that leads to less oxygen entering our lungs.

Why do Most of us Breathe from our Chest, Not our Diaphragm?

So why does this happen in the first place? There are a lot of answers for this.

For many of us, one big reason is simply our culture. When we breathe with our diaphragm, the diaphragm drops down and creates that negative pressure in the lungs -- but what it also does is that it increases the pressure in our belly -- which makes our belly expand.

If you think of every article you've ever read about losing weight, how to dress attractively, or every depiction of an attractive person in our media, you'll be quickly able to note that an expanded belly is never a part of any of those messages about how to look great. From a very young age, we have modeled for us that we must always suck in our bellies -- to appear skinny. This is a very strong cultural message, and in my opinion, is one of the primary underlying reasons for these chest-breathing strategies.

What can we do to change this Breathing Pattern and Start Using our Diaphragm to Breathe?

So now that we know what the problem is, how do we fix it?

FIND Your Diaphragm

The first thing we have to do is get in touch with our diaphragm muscle. Let me give you a great exercise that will help you do just that.

After learning how to feel your diaphragm, you want to go right into learning how to use it to breathe.

Use Your Diaphragm to BREATHE

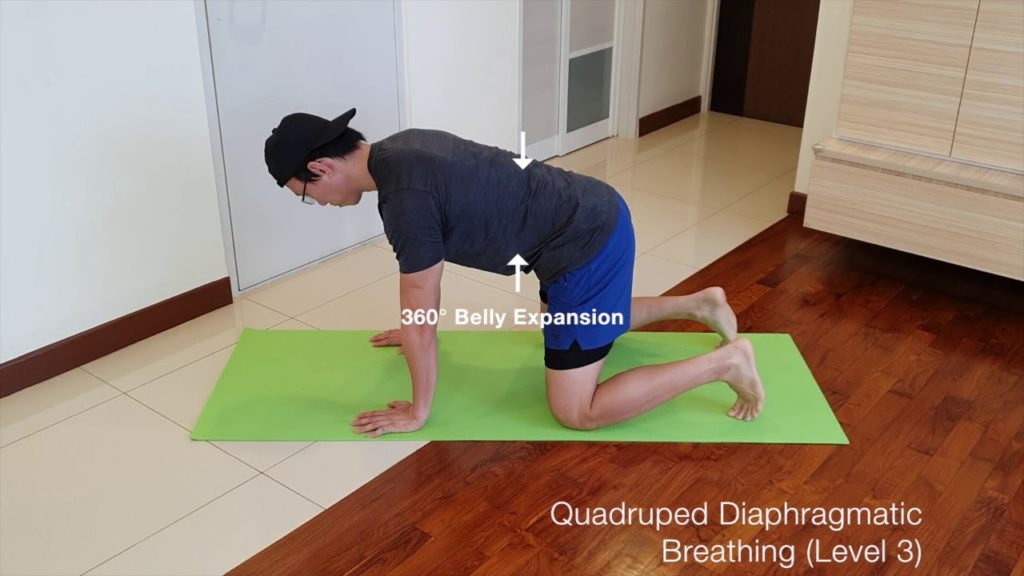

Lying on your back is the easiest position to use as you first start to practice proper breathing mechanics; that's because it allows most of your muscles to relax since you're not having to resist gravity. But that's not usually a position that we're in much of our day -- so it's important that we also learn to do this same type of breathing in other positions.

If you take the time to work on each of these exercises for two to three weeks, and then move on to the next one listed, I promise you that you'll begin to notice less tension in your neck and chest.

Why not spend 3-10 minutes a day doing this Breathwork to give your neck and chest muscles a new possibility of Relaxing while your diaphragm does the work it was designed to do? You won't regret it!

If you need more help with your neck pain or any other pain, Movement Laboratory is here to help! Give us a call at 918-300-4084 and schedule your appointment today. During the month of November, we are having a special for a free exam on your New Patient visit. That's an $85 value! Don't let pain interfere with your Holidays, come see us today!